Home

A Broad Introduction

Allergy Concepts

Food Issues

Asthma

Rhinitis & Hay Fever

Eczema

Children & Infants

Allergy to Animals

Finding Answers

|

Was this the answer

to the dust mite problem?

Introduction

It is obvious that anything which will kill mites without

undesirable effects on patients could be a popular and effective way

to deal with the ubiquitous dust mite, because avoidance of the most

important allergen world-wide is so often difficult, expensive, or

impossible. From 1988 to 1994 I personally conducted clinical trials

of a German product called Acarosan which contains benzyl benzoate

to kill the mites, plus a mixture of detergents to make the mite

faeces stick together, and is presented either as a spray or a

powder which is applied to bedding, carpets, and soft furniture. My

trials were remarkably effective but the results are not acceptable

for publication because nowadays all trials have to be carried out

on a double blind basis, when neither doctor nor patient know if the

material they are using contains the active agent or an inactive

placebo. It is obvious that anything which will kill mites without

undesirable effects on patients could be a popular and effective way

to deal with the ubiquitous dust mite, because avoidance of the most

important allergen world-wide is so often difficult, expensive, or

impossible. From 1988 to 1994 I personally conducted clinical trials

of a German product called Acarosan which contains benzyl benzoate

to kill the mites, plus a mixture of detergents to make the mite

faeces stick together, and is presented either as a spray or a

powder which is applied to bedding, carpets, and soft furniture. My

trials were remarkably effective but the results are not acceptable

for publication because nowadays all trials have to be carried out

on a double blind basis, when neither doctor nor patient know if the

material they are using contains the active agent or an inactive

placebo.

Double blind trials to assess the effectiveness of a remedy are

ideally suited to testing a new drug, but when applied to an

acaricide for killing mites creates difficulties which resulted in

several inconclusive publications. The reason may be that the

patients chosen were not selected in pairs carefully

matched for their sensitivity to mites and the severity of their

allergies before being allocated to the placebo group or the active

group of patients. Without this precaution, which has not to my

knowledge been applied in any trial, it would be easy to introduce

unintentional mismatch in the severity of asthma, rhinitis, or

eczema in the two groups of patients, and seriously distort the

result. Also, no double blind placebo controlled clinical trial

could last for from one to five years, as mine did!

I have had one paper published in an American Journal, and presented

the results by lectures by detailed posters at Allergy Society

meetings in the UK, Europe, and the USA. In spite of all this

publicity within the profession I have found little or no interest

amongst colleagues in Britain, which I find difficult to understand.

Other Acaricides available here in supermarkets have never been

assessed in any sort of trials, and I have never had any good

reports

One might imagine that in spite of medical disinterest Acarosan

would have become popular and widely used. However marketing was

initially limited to clinics because the active principle is Benzyl

Benzoate, and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) were concerned

about possible toxicity of this substance. The HSE made repeated

demands for many very expensive toxicity tests which did not make

sense because Benzyl Benzoate had been passed as safe for use in

food in the USA in 1965, had been approved in Europe to a

recommended daily intake of up to 5mg per kilo body weight in 1970,

and finally by our Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food (MAFF)

in 1978.

By the time the HSE

granted full approval five years later the vendors, who had spent a

great deal of money satisfying the requirements of the HSE, had lost

interest in marketing the product. Acarosan also fell foul of the

Food and Drug Administration in the USA for the same reasons, and

sales in the USA were prohibited. Unfortunately no other company

wanted to market it, so it has not been available in the UK since

1994, but could be obtained from Germany, where Social security paid

for Acarosan until recently, when it was withdrawn because of lack

of proof of efficacy.

At one time it was hoped that when Acarosan had been shown to be an

effective mite killer it would become prescribable by the NHS as a

method of dealing with the mite allergy problem. Benzoate has again

been banned in Europe because of safety concerns and its cost was

reimbursed in Germany for many years. At one time it was hoped that when Acarosan had been shown to be an

effective mite killer it would become prescribable by the NHS as a

method of dealing with the mite allergy problem. Benzoate has again

been banned in Europe because of safety concerns and its cost was

reimbursed in Germany for many years.

The concept of

treating the home of the patient with Acarosan instead of treating

some of the inhabitants of the house with expensive drugs seemed to

make sense, and might have saved many millions of pounds from the

NHS drug bill. Unfortunately there seems to be no possibility that

this would ever happen here, where expensive drugs are routinely

accepted as the only treatment.

This lack of interest seems surprising because, since desensitising

injections became forbidden in the UK nearly twenty years ago, no

specific and potentially curative treatment has been available for

mite allergic patients in this country, which probably has the

highest incidence of mite allergy in the world. Avoidance of the

ubiquitous mite, which is practically impossible to eradicate, is

the obvious answer. Some double blind trials have found in favour of

very expensive mattress and pillow covers, so they are often

recommended.

The first time I reported the remarkable results I was

obtaining with Acarosan at a British Allergy Society Meeting a

medically qualified person, who works for a drug company, said to my

wife at dinner that evening “I do not understand why your husband

wants to kill our best friends” A revealing remark?

My long experience with Acarosan has convinced me that it is really

effective, and that mismatch of the groups in the double blind

trials is the reason why they were inconclusive. I now present my

results using the patients as their own controls, hoping to

stimulate interest in this approach to the world wide problem of

dust mite allergy. This appears to be a practical, non toxic, and

relatively inexpensive approach to the problem, but in meanwhile the

Pharmaceutical Industry and the manufacturers of bedcovers will

continue to thrive. I must declare that I have no financial or other

interest in the promotion or sale of Acarosan, and that I was not

paid for the clinical trial.

To the practising physician the dust mite problem presents great

difficulties in management. Total avoidance by relocation to a high

dry climate, such as Switzerland where the mites cannot thrive, is

rarely possible. Very few patients are willing to throw out their

fitted carpets, soft upholstered furniture, duvets, blankets, and

pillows and put up with bare boards, linoleum, tiles, or (more

recently) laminated floors--- and perhaps also get rid of their pets

who have become part of the family. All this especially if there is

no guarantee that these extreme and expensive measures will be

effective.

The major source of mite allergen is the bed and mattress, where

every night we supply warmth, humidity, and skin scales from our

bodies as mite food. In their turn the mites produce the faecal

pellets which are the source of the major allergen. Special

mattress covers are too expensive for impoverished patients in bad

housing conditions who are most in need of them. Quality of covers

is variable and the mattress is not the only source of mites, which

can make themselves a home in any sofa, and in the depths of the

fitted carpet. Measures to reduce the humidity to a level which will

inhibit the multiplication of the mites are neither comfortable nor

practical and very expensive. The major source of mite allergen is the bed and mattress, where

every night we supply warmth, humidity, and skin scales from our

bodies as mite food. In their turn the mites produce the faecal

pellets which are the source of the major allergen. Special

mattress covers are too expensive for impoverished patients in bad

housing conditions who are most in need of them. Quality of covers

is variable and the mattress is not the only source of mites, which

can make themselves a home in any sofa, and in the depths of the

fitted carpet. Measures to reduce the humidity to a level which will

inhibit the multiplication of the mites are neither comfortable nor

practical and very expensive.

It is obvious that the only sensible solution is to apply an

acaricide to kill them off as often as necessary, but no double

blind trials have produced a clear result, probably due to mismatch

in the severity of the allergy in the two groups. This failure to

produce a clear result, plus the regulatory authorities anxieties

about the toxicity of a spray or a powder containing a substance

allowed in many soft drinks, has had the effect of discouraging the

use of acaricides. If the acaricides contained potent insecticides,

such as are contained in ordinary fly sprays which are used

frequently in many homes, then it would make sense to be cautious.

A recent and very comprehensive European review of the effectiveness

of the many methods of control of mite and pet allergies reached the

conclusion that there was little evidence to support the use of any

physical or chemical methods of control of dust mites or pet

allergens, based on published double blind placebo controlled

trials. This result clearly suggests that in this country dependence

on drugs is total, and that attempting to control mites is a waste

of money. A recent and very comprehensive European review of the effectiveness

of the many methods of control of mite and pet allergies reached the

conclusion that there was little evidence to support the use of any

physical or chemical methods of control of dust mites or pet

allergens, based on published double blind placebo controlled

trials. This result clearly suggests that in this country dependence

on drugs is total, and that attempting to control mites is a waste

of money.

Patients often require medication for life to control the effects of

the mite faecal particles in their environment. This is because

attempts to control mite infestation are relatively ineffective, and

the mite can produce up to 200 times its own weight of faeces in its

life-time. The full scientific name for the species of mite

commonest in England is Dermatophagoides Pteronyssinus, and the

faeces contain the major allergen, which is referred to as Der P1.

Several other allergens contained in the mite and its products have

been isolated since 1994, but Der P1 is the most important, and

measurement of Der P1 in house-dust gives an accurate assessment of

the extent of mite infestation

So, should we just give up trying to control the allergens in the

environment, and depend entirely on suppressive drugs? In my opinion

this would be to accept that we must await the day when it will be

possible to stop patients reacting to environmental allergens by

desensitising them. This could be accomplished either by the

time-honoured method of injections of gradually increasing doses of

allergen in common use everywhere in the world except the UK, or

perhaps by using the self-administered sublingual method of

desensitisation against mites which has

been established to be free from risk by double blind trials in

Europe. Modified allergens treated to

make any reactions to injections much less likely have recently been

developed and subjected to successful trials in Europe, and offer

another possibility. Unfortunately it is likely that introduction of

self-administered SLIT for desensitisation against mites will take

many years because of the restrictions imposed on clinical trials in

this country.

The Clinical trial of Acarosan The Clinical trial of Acarosan

I will now present a brief account of the clinical trial from 1988

to 1993, based on poster presentations and talks given at Allergy

Society meetings in the UK, Switzerland, and the USA. None of these

presentations attracted any interest, and the product has been

unobtainable in the UK since 1994. This account of the trial is

presented in a narrative fashion so that it may not present any

difficulties for the reader.

80 patients were involved in the trial for periods of from one to

five years. Half of them were already well known because they had

been seen regularly by me for from 2 to 17 years. They had all been

investigated in depth and in detail, and all were dependent on

suppressive drugs for symptom control. 33 were allergic to mites

only, and the rest had multiple sensitivities. The group were

typical of any allergy clinic dealing with allergies affecting any

part of the body.

The results were assessed by symptoms diaries kept by the patients,

and daily peak flow measurements in asthmatics. At regular intervals

the amount of mite allergen in samples of house dust was measured by

a colleague who did not know the origin of the samples. I also

assessed. the amount of mite in the dust by the size of skin test

reactions to extracts of the dust samples which patients brought to

each consultation.

These patients acted as their own controls by comparing their

clinical symptoms charts, the amounts of mite allergen in the dust

from their beds, and the size of skin test reactions to extracts of

their own dust, for some time before and at intervals after using

Acarosan. One application was found to be effective for as long as a

year, probably because it has been shown that the mites eat their

own faeces, thus recycling the Benzyl Benzoate and prolonging its

effectiveness.

Assessment of the patients status took account of all body systems

involved, need for medication, and peak flow charts for asthmatics.

Special attention was paid to other factors such as pets and food

allergies or intolerances. At every visit samples of general

house-dust and bed dust were submitted, and used to make 10%

weight/volume extracts for skin testing as described elsewhere on

this website. These dust extracts were used for prick skin testing,

using Morrow-Brown Standardised skin test needles, for comparison

with the reaction to a standardised dust mite extract. The wheals

produced by the skin test reactions were outlined with biro, and

transferred to the records using document repair tape. The amount of

Der P1 mite allergen in the dust extracts was measured by Dr Terry

Merrett, using monoclonal antibodies donated by Professor Martin

Chapman of Charlottesville USA.

Once a satisfactory baseline of symptoms and treatment had been

established a supply of Acarosan was issued with full instructions

and a video on its use on bedding, mattress, carpets, and soft

furniture. No other methods to control mites were used, and no

change in cleaning routines was suggested. Acarosan was not used

again until there was evidence that further application was

necessary, as shown by Der P1 assay, skin tests using extracts of

patient’s own dust, or increasing symptoms.

|

|

|

|

Average

Levels of Der P1 at Intervals

After Applying Acarosan

|

Mean

Diameters of Prick Test Reactions to 10% w/v

Extracts of Patients Dust Samples

Average weal to Pharmacia D. Pteronyssinus was 10.3mm

(16mm -6mm)

|

It

was very surprising that the effects of one application of

Acarosan lasted so long. It

was very surprising that the effects of one application of

Acarosan lasted so long.

The explanation was that they eat their own

faeces, thus recycling the benzyl benzoate which kills them off.

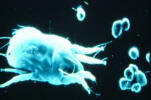

On

the left is a video still donated by Dr J Rees where a mite is seen

with a faecal pellet in its jaws.

On the right a fluorescent dye was attached to the benzyl benzoate

so that is could be seen under fluorescent light.

The tagged

benzoate is easily seen in the gut of the mite.

Illustrative Case Histories Illustrative Case Histories

The results of the trial will be discussed at the end of this

section, but the story of Acarosan is best told as a narrative as

far as possible, with details of remarkable cases to illustrate

various important points

John was 19, and was first seen when he was three with rhinitis,

asthma, and eczema due to dust mite, dogs, and horses. By 1988

control was becoming more difficult, with increased sneezing,

blockage, itchy eyes, itchy palate and ears, and eczema. Three days

after treating bedroom and living room with Acarosan these symptoms

all disappeared and no treatment was required for the first time in

16 years. A month later exposure to a dirty old motor coach and an

unclean foreign hotel caused a temporary relapse of all the

symptoms, including the eczema, as shown by his excellent charts.

This unexpected challenge emphasised the dominance of the mite

allergen in all his complaints. On return home he had no problems

for 11 months, when a recurrence of his symptoms was associated with

an increase in the skin reaction to an extract of his own dust, and

in the Der P1 assay, so more Acarosan was issued. He then remained

symptom free for another three years when he had a slight relapse of

the rhinitis and the eczema, which cleared after using acarosan on

his surroundings. By 1992 he was at college, had ceased to need

inhaled steroids, and was active in sport without asthma.

Allan was 46 when he joined the trial in 1991 with a history of

asthma and rhinitis since age 17 well controlled with Becotide and

Ventolin inhalers and an average Peak flow of 405l/min. His son

David aged 13 had had asthma and rhinitis for 5 years, effectively

suppressed with the same medication, and an average peak flow of

365l/min, but exercise induced asthma prevented him playing any

games. In both father and son skin tests were markedly positive for

mites, and both had RAST 4+ for mites.

After the house was treated with Acarosan father’s peak flow rate

did not increase and he needed the same medication, as repeated

efforts to reduce medication were ineffectual, but exposure to dust

in the house did not affect him as it had done previously. Treatment

of the house had a striking effect on son David, as within two

months he was able to stop all treatment except for an occasional

puff of Ventolin, and he could play sport with no exercise asthma.

After a year his average peak flow was 364 without any treatment at

all, and he.has remained free from asthma ever since. After two

years he entered for the 1500 metres at the school sports, and then

discovered that he had left his ventolin inhaler at home. He did not

panic, and won the race without even a wheeze.

His elder brother had no allergy problems so his room was not

treated until he complained that mites were crawling across the

viewfinder of his new camera, and he captured a few which were

identified as Lepidoglyphus destructor, the species of mite which is

usually found on farms. The dust from his room assayed very high,

and an extract of his room dust produced a reaction on his father’s

skin 17 mm in diameter, but produced none at all on his own skin as

he was not an allergic person. The reason for the infestation was

that he ate biscuits when studying, and destructor loves to live on

cereal., so his room was also decontaminated.

David has continued to be free from asthma and is now aged 29. Until

age 19 both skin and blood tests remained very positive without

symptoms to match, while the assay of his dust remained very high,.

a finding which could have been very confusing. Clearly he had

adapted successfully and no longer reacted to mites, perhaps because

a window of a relatively mite free environment had been created for

a few years. He seems to be a definite cure.

Father Allan also recovered, as five years later he had stopped his

Becotide and his peak flow rates were 455, but the skin tests were

still very positive. Ten years later he is well on inhaled treatment

only.

A very serious Eczema problem A very serious Eczema problem

Stephen was 29, and had had eczema for three years which was so

severe that three different dermatologists could offer no

alternative except indefinite oral steroids and steroid creams. When

first seen he had severe generalised weeping eczema, was almost

suicidal, and was taking 10 mgms of prednisolone daily. Prick skin

tests were very positive for mites, and also to an extract of his

own bed dust, which assayed at 229 micrograms of Der P1. This is

very high, as 5-10 micrograms is unacceptable in the home of a mite

allergic patient. Following the use of Acarosan in bed, bedroom, and

living room he was able to stop oral steroids and was about 80%

improved in a month. Stephen was 29, and had had eczema for three years which was so

severe that three different dermatologists could offer no

alternative except indefinite oral steroids and steroid creams. When

first seen he had severe generalised weeping eczema, was almost

suicidal, and was taking 10 mgms of prednisolone daily. Prick skin

tests were very positive for mites, and also to an extract of his

own bed dust, which assayed at 229 micrograms of Der P1. This is

very high, as 5-10 micrograms is unacceptable in the home of a mite

allergic patient. Following the use of Acarosan in bed, bedroom, and

living room he was able to stop oral steroids and was about 80%

improved in a month.

By 3 months he had cleared completely, and

remained clear without any treatment until he spent a weekend in a

dirty and dusty flat. After the first night he began to itch, and

after the second night he had a severe relapse of the eczema lasting

two weeks and requiring a course of oral steroids. During the next

two years the eczema cleared up completely, in spite of the fact

that the amount of Der P1 in the dust increased to 33 micrograms,

and his brother developed asthma due to mites.

His eczema did not

relapse until the Der P1 reached 98.5 in November 1991, cleared

after using Acarosan, and relapsed again in 1992 when the Der p1

reached 133 micrograms, but cleared in two weeks after Acarosan.

Subsequent follow-up to 1995 revealed that slight relapses occurred

every year which were abolished by using Acarosan. Further contact

has been lost.

An Eczematous Family Affair An Eczematous Family Affair

Alan aged 29 and his two daughters aged 21/2 and 4 years all had

eczema. The younger child cleared completely on avoiding egg, but

the elder child had a big skin reaction to mite, and also to a

family dust extract, which assayed at 28 micrograms of Der P1. At

first another acricide (Allerex) was applied, but after using no

less than 4 litres there was only slight improvement in the eczema

and in the skin reaction to the family dust extract, but the assay

was down to 5 micrograms. Acarosan was then introduced, and after 6

weeks there was no skin reaction to the family dust extract, which

assayed at 2,2 mcgms, Father’s life-long eczema subsided, his hands

were clear for the first time in his life, and daughter cleared

completely. The skin tests shown were carried out on the father’s

skin. A few months later a new wool carpet was laid. After six weeks

eczema recurred on the child’s knees, but cleared after acarosan was

applied to the new carpet, suggesting that it had become colonised

by mites in that short time. Alan aged 29 and his two daughters aged 21/2 and 4 years all had

eczema. The younger child cleared completely on avoiding egg, but

the elder child had a big skin reaction to mite, and also to a

family dust extract, which assayed at 28 micrograms of Der P1. At

first another acricide (Allerex) was applied, but after using no

less than 4 litres there was only slight improvement in the eczema

and in the skin reaction to the family dust extract, but the assay

was down to 5 micrograms. Acarosan was then introduced, and after 6

weeks there was no skin reaction to the family dust extract, which

assayed at 2,2 mcgms, Father’s life-long eczema subsided, his hands

were clear for the first time in his life, and daughter cleared

completely. The skin tests shown were carried out on the father’s

skin. A few months later a new wool carpet was laid. After six weeks

eczema recurred on the child’s knees, but cleared after acarosan was

applied to the new carpet, suggesting that it had become colonised

by mites in that short time.

One year later the family moved to a completely renovated old house

with more space, taking with them all the treated carpets and

furniture. Within four months the elder child’s eczema was

reappearing, and she had her first asthma arrack. Her sister aged 2,

whose eczema had previously disappeared after avoiding egg, now

developed slight eczema. The assay of the Der P1 in the house dust

of their new house was found to be 24 micrograms, nearly as high as

the first assay before the previous house was treated. Skin testing

revealed that she had now become positive to both mite extract and

to bed dust extract, yet she had been negative only a year before.

With liberal use of Acarosan the itching, scratching, and eczema

cleared up, and three years later eczema had not recurred in any

member of this family. This family affair shows how closely mite

infestation can be related to the eczematous reactions of a family

living in a Victorian house with more accommodation which must have

had an unseen and unsuspected population of mites which re-infected

their bedding, furniture, and carpets, previously treated with

Acarosan.

A long-standing case of eczema A long-standing case of eczema

|

Mary was first seen aged 26 with severe hand eczema, due to dust

mite and was carefully desensitised with considerable improvement

for five years, but slowly deteriorated until seen again aged 44.

She had been hoovering her five year old mattress regularly

every few weeks as

instructed.

The skin test reaction to the standard mite extract was

12mm across, but to her own dust extract it was 17mm, with a severe

delayed reaction the next day.

Her dust was found to be loaded with

faecal particles in spite of the fact that another acaricide,

Actomite, had been used on bed and bedding a month before, and the Der P1 assay was very high at 312 micrograms.

The microphotographs

show the remarkable decrease in faecal particles after only 21 days

and in the skin test reaction.

Further follow-up was not possible |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Skin reaction to dust extract after 21 days using Acarosan |

A Mite Infested House can cause Severe Eczema A Mite Infested House can cause Severe Eczema

Mark was 35 and had had mild eczema since infancy, as had mother and

brother. Four dermatologists had been consulted at various times.

One did patch tests which showed nickel sensitivity, but none did

skin prick tests. He had been much worse since purchasing an old

damp house and spending much time renovating it. A local

dermatologist had admitted him to hospital twice, and he had had

oral steroids several times in the previous year.. The only

occasions when he had been better was when camping, or when in

hospital for a week without treatment, only to relapse within two

days on return home.

When seen he had very severe weeping eczema requiring oral steroids

for control. Prick skin tests were +++++ for two species of mite and

for his own dust extracts. His Total IgE was the highest ever seen

at 43,000 units ( normal maximum about 100) with specific IgE ++++

for 5 species of mite. He saw mites crawling on a black surface, and

captured some for identification. Attempts to control the

infestation with acarosan were relatively ineffective, which was not

surprising because the previous owners had covered many walls with

polythene and stuck wallpaper on top, the whole acting like blotting

paper in damp areas Four months later he moved to a modern flat with

new carpets and furniture. He stopped itching in a week, and the

eczema was negligible by three weeks. In this case the infestation

was so bad that the acaricide could not control it. The lesson is

that anyone with mild eczema would be unwise to buy an old house,

especially if damp.

Asthma and Rhinitis Asthma and Rhinitis

Deborah was first seen aged 17 with asthma for 3 years due to mites

and was successfully desensitised, but 12 years later, after

injections for asthma were forbidden, she relapsed and became

difficult to control requiring frequent courses of oral steroids.

Her bed dust assayed at 199 micrograms of Der P1, but after

Acarosan was applied all treatment ceased. The only exception was

that when she visited her parents, who had an old dusty house, she

always reacted with sneezing and wheezing. She has remained easily

controlled even after Acarosan became unobtainable

Andrew was aged 15 with severe asthma and rhinitis controlled with

steroid inhalers and bronchodilators, peak flow average 450. Three

months after using Acarosan all treatment ceased without relapse,

peak flow averaged 500, all symptoms were absent for the first time

In 5 years, and he was able to play football without asthma.

Acarosan was used for two years only. The only time he had an attack

of asthma was after attending a concert in an old theatre, and after

accidental exposure to a dust sample in my consulting room ! His

mother was also a dust allergic. She had wheezed every night for 14

years, but ceased after Acarosan was used.

The Der P1 assay in his bed was 179 micrograms to begin with,

falling to very low levels after Acarosan. Two years later he went

off to college, and neither asthma not rhinitis relapsed in dusty

students lodgings, and he was able to play football without any

problem. Aged 20 he was apparently cured of his asthma as he did not

relapse even when his bed dust contained 41 micrograms/Gm, a very

high reading well over the recognised upper limit for mite

infestation as a cause of asthma.

Summary of Results

Is Acarosan an effective answer to the mite problem? Is Acarosan an effective answer to the mite problem?

I had been very interested in mite allergy since 1968, when I

published the first study from this country confirming that the mite

was the major allergen in house-dust, in spite of much scepticism at

that time. The story behind this trial is that when attending a

meeting in Washington D C in 1985 I heard a presentation on Acarosan

which was so interesting that I made a firm contact with the speaker

afterwards. I heard nothing more for two years, when the

manufacturers wrote asking if I could put them in touch with a

company in the UK to market their product. I made enquiries on their

behalf but found no interest whatever. They supplied me with many

copies of a video regarding the mite and Acarosan, which I sent to

prominent members of the British Allergy Society, but nobody seemed

to be interested. Finally a small pharmaceutical company agreed to

market it, and supplied enough for an open clinical trial. The

comment from an employee of a drug company after the first

presentation of my results that I was “killing their best friends”

is revealing.

The improvements correlate well with the decrease in skin tests and

allergen in the dust samples lasting for at least a year. The

persistence of the acarosan because of the nasty habits of the mites

recycling the acarosan was an unexpected finding of great

importance, as treatment of the house about once a year or when

required is much more acceptable. Recurrence of symptoms on exposure

to untreated houses, hotels, and theatres is important evidence

confirming the persistence of allergy to mites, and also confirmed

that the improvements are due to the Acarosan. Treating the house

instead of the treating the inhabitants for life with expensive

drugs is a concept which could save many millions from the NHS

budget because mites are such a common cause of allergic problems.

Improvements in asthma, rhinitis, or eczema in children living in

the same house as a patient were noted in ten instances was an

unexpected bonus which supports the concept of treating the

environment instead of the patient..

Less than half of the patients had a solitary allergy to mites, the

rest being sensitive to a range of other environmental allergens and

sometimes foods as well. Almost total abolition of mites from the

home for a prolonged period has not been achieved before, and has

enabled better understanding of the relative importance of mites,

pets, and foods in the causation of allergic disease. Results in the

more complex cases were not as good as in the 33 cases where mite

was the sole cause, emphasising the difficulties in assembling a

homogeneous group of allergic patients suitable for a double blind

placebo controlled trial, and also keeping them motivated for long

enough to get a clear result. Entrants to any trial in allergy must

be fully assessed by a clinical allergist, and ideally only pure

mite allergics accepted and sorted into matched pairs for severity

of symptoms

The results in eczema are the most dramatic and gratifying, and

confirm the importance of mites as a cause of eczema. In the face of

this evidence it is even more difficult to understand why British

dermatologists still seldom accept that allergy is a very important

cause of eczema, and are unwilling to carry out prick skin tests.

Perhaps the reason is that some departments may have facilities only

for patch testing. The remarkable potency of 10% bed dust extracts

suggests that when eczema sufferers are in bed at night, when the

itching is at its worst, mite faecal particles on the skin require

just a trace of sweat to produce a very strong mite extract which

penetrates the cracks in skin which is already damaged, causing

intense continuous skin reactions, scratching, and infection.

The most important finding by far is that in some young patients

sufficiently prolonged absence of mites in the environment

eventually brings about re-adaptation and tolerance, so that they no

longer react to untreated environments and are able to stop all

medication without relapse. This phenomenon has also been observed

in Europe in some children who have had prolonged stay at schools in

the Alps where the mites cannot survive.

It is very gratifying to have actually cured some of these allergy

victims, and it seems a great pity that this method of mite control

has not been used more widely. These results suggest that if mite

control could be used more often in children they would have a

chance of escaping from the allergic march. |